Python debugging

Table of Contents

the ‘code’ for this article can be found here: https://github.com/peter-mcconnell/petermcconnell.com/blob/main/assets/dummy/pydebug/main.py

debugging Python - the context⌗

This is the flow I take when faced with a new Python codebase. I often find myself having to debug codebases I’ve never seen before which has forced me to become very comfortable being lost in code and to develop some patterns that help me find my way. This is what I’m sharing with you today.

I should note that I live in terminals - constantly connecting to servers, containers, colleagues machines, my own homelab etc. To compound this fact my editor of choice also lives in the terminal (Neovim). For that reason this guide is TERMINAL based and as such does not include IDE-based debugging flows (which are solid from what I’ve seen).

what are the requirements?⌗

The debugger of choice (for me) is ipdb. The reasons for this are at the end of the article.

Install ipdb:

pip3 install --user ipdb

We’ll also need to gather information from the refining scope section below.

refining scope⌗

Often (my own usecase) my Python debugging story typically starts with: “This app is broken. It’s doing X” which tells me very little about what’s wrong and where to look. My first objective is to make the size of the problem statement as small / tight as possible. To do so, before I’ve looked at any code I try to do the following:

- validate that it appears to be an issue with the code and categorise it

- perf issue

- logic issue

- flakiness

- dependency issue

- etc

- identify which version of that app I need to debug & where I can get it

- identify which part of the codebase (file location, method, line)

- identify required inputs (method arguments, environment variables, third party sources etc)

- understand what has been tried already to fix the problem

- identify stakeholders, urgency etc …

This serves a few purposes:

- ensure I can reproduce the bug

- reduce the scope of things that I need to look at

- help me understand the business logic / expected results

At this point I should have the confidence to know that the problem requires debugging.

example application⌗

To get started create the following file. This is the simplest possible example I could create so as to keep signal/noise ratio in favour of the actual debugging steps:

#!/usr/bin/env python

# main.py

def doubleit(val):

return val * 3

if __name__ == "__main__":

print("doubleit 2: %d", doubleit(2))

print("doubleit 4: %d", doubleit(4))

print("doubleit 8: %d", doubleit(8))

We’ll use this simple example for our debugging.

using ipdb⌗

From the information gathered earlier lets imagine the outputs were that the program above is spitting out the wrong values. We expect the doubleit lines to show their values being doubled but instead they seem to be trebled (yes, it’s obvious why, but imagine this is a very large program and you don’t know why the output is what it is).

With that information to hand we can look for the doubleit method and add set some breakpoints so that we can explore the program as it’s running to understand the state:

#!/usr/bin/env python

# main.py

def doubleit(val):

import ipdb # < added this line

ipdb.set_trace() # < added this line

return val * 3

if __name__ == "__main__":

print("doubleit 2: %d", doubleit(2))

print("doubleit 4: %d", doubleit(4))

print("doubleit 8: %d", doubleit(8))

We can continue to add ipdb.set_trace() points throughout our code. Generally speaking when I am running this for the first time I’ll tend to just drop one or two points in the codebase that I know are going to be in the path, with the expectation that I’ll manually step through the execution to learn how it flows. When we’ve added all of the breakpoints that we need we can instruct the program to run with python main.py:

$ python main.py

> /home/pete/go/src/github.com/peter-mcconnell/petermcconnell.com/assets/dummy/pydebug/main.py(6)doubleit()

5 ipdb.set_trace()

----> 6 return val * 3

7

ipdb>

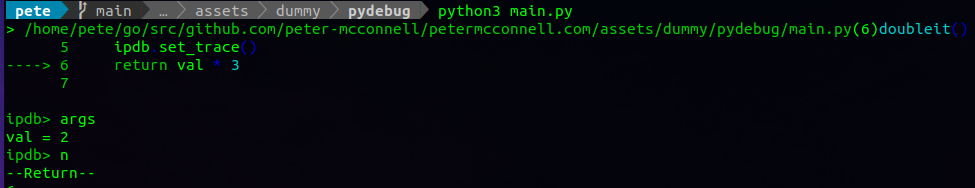

Now we’ve ran our program with an attached debugger and it has paused execution at the breakpoint we set. We can run args to see which arguments where passed to the method:

> /home/pete/go/src/github.com/peter-mcconnell/petermcconnell.com/assets/dummy/pydebug/main.py(6)doubleit()

5 ipdb.set_trace()

----> 6 return val * 3

7

ipdb> args

val = 2

So in this point in the program we’re in the doubleit method when it was invoked with a val value of 2. We can print this and other variables using p:

ipdb> p val

2

or just the variable name on its own:

ipdb> val

2

We can even call methods from this point:

ipdb> doubleit(6)

18

To walk over the execution we can press n to go to the next point of execution:

ipdb> doubleit(6)

18

ipdb> n

--Return--

6

> /home/pete/go/src/github.com/peter-mcconnell/petermcconnell.com/assets/dummy/pydebug/main.py(6)doubleit()

5 ipdb.set_trace()

----> 6 return val * 3

7

and view the backtrace with bt:

ipdb> bt

/home/pete/go/src/github.com/peter-mcconnell/petermcconnell.com/assets/dummy/pydebug/main.py(9)<module>()

8 if __name__ == "__main__":

----> 9 print("doubleit 2: %d", doubleit(2))

10 print("doubleit 4: %d", doubleit(4))

6

> /home/pete/go/src/github.com/peter-mcconnell/petermcconnell.com/assets/dummy/pydebug/main.py(6)doubleit()

5 ipdb.set_trace()

----> 6 return val * 3

7

To view the code around the current point of execution just press l:

ipdb> l

1 #!/usr/bin/env python

2 # main.py

3 def doubleit(val):

4 import ipdb

5 ipdb.set_trace()

----> 6 return val * 3

7

8 if __name__ == "__main__":

9 print("doubleit 2: %d", doubleit(2))

10 print("doubleit 4: %d", doubleit(4))

11 print("doubleit 8: %d", doubleit(8))

Which of course shows our very hard to find logic error, * 3 instead of * 2.

Note: you can also set breakpoints in the stdlib functions (paths will vary depending on your setup):

ipdb> b /home/pete/.local/lib/python3.10/site-packages/requests/api.py:14

Breakpoint 1 at /home/pete/.local/lib/python3.10/site-packages/requests/api.py:14

debug flow⌗

Using the commands above I can begin my cyclic process of narrowing in on the fix:

repro -> explore -> understand -> tweak -> repeat

More often than not this means I only need to understand a very small part of the application and can ignore code that isn’t relevant to the immediate issue.

At a more detailed level this process looks like:

- (repro) write a test that triggers the bug in as simple terms as I can express

- (explore) set breakpoints

- (explore) run

pytestwith the-sflag so that I can interact withipdb - (explore) use

argsto check the arguments for the method that I’m in - (explore) print surrounding variable values

- (explore) ensure the state of the program makes sense for my current breakpoint. If not, I need an earlier breakpoint. If so, continue with

n - (explore) repeat these steps until I’ve reached the point that the program is in a seemingly erroneous state

- (understand) it’s at this stage I’ll take time to properly read the surrounding code and experiment with variable values to see if I can get the program to act in the expected manner

- (understand) depending on the category of bug I’ll look for algorithmic complexity issues, stack overflow issues, parameter edgecases, logging quality, randomness factors etc. This is when the editor setup shines. see neovim section

- (tweak) I’ll make minor adjustments to the code which I believe will nudge the program into the right place

Once I’m happy that my small tweaks are having the desired effect I’ll perform some tidy ups and look for opportunities to harden the code with type checking / improved logging / more tests.

neovim⌗

This section describes my neovim configuration for Python debugging at a high level. In short my debugging / code exploration flow boils down to:

telescopehttps://github.com/nvim-telescope/telescope.nvim- allows me to

ctrl + fscan directories for files - allows me to set up keybindings for scanning any common directories

- allows me to

cochttps://github.com/neoclide/coc.nvim- code complete in all of the languages I need

- function descriptions

gd- default vim keybinding for go-to-definition. Jumps me into a function that I’m wanting to understandctrl + o/ctrl + i- default vim keybindings for go to last / next jump point. Really useful as I’m scanning code - I can keep jumping through definitions withgdthenctrl + omy way back /ctrl + imy way back down as I’m trying to build an understanding

You can see my full Neovim config here: https://github.com/peter-mcconnell/.dotfiles/blob/master/config/nvim/init.vim

summary⌗

The example above is extremely trivial - where ipdb and it’s ilk shine are on complex usecases where you may not even know what methods are between the input and output, such as debugging the stdlib. Just this week I used ipdb to identify why a codebase long forgotten was throwing an obscure error for a given dataset. By using ipdb I reproduced the scenario and just before the point at which I knew it would error created a break point that allowed me to inspect program state and better understand the conditions leading to the error, resulting in a quick patch.

why not pdb?⌗

Bells and whistles; I like that ipdb has better color support and tab completion. You could absolutely get the same results with pdb.